For the first time in Palm Springs Modernism Week’s 19-year history, architect Richard Neutra’s iconic Kaufmann Desert House opened to the public in February. When tickets became available in December to tour the home’s landscape during this year’s annual festival of modern design, architecture, art, fashion and culture, they sold out in three minutes.

Only a glimpse of the house is visible from the street, but the home has been world-famous since Julius Shulman photographed it in the 1940s, with the San Jacinto Mountains as the backdrop. Later, photographer Slim Aarons captured the home — and some say the spirit of modernism — in his 1970 photo Poolside Gossip.

The recognizable pool was only one portion of the landscape featured on the tour, as the property has four distinct courtyards designed to accommodate specific uses, microclimates and privacy needs. All have been meticulously restored, and we’ll be touring them here.

Only a glimpse of the house is visible from the street, but the home has been world-famous since Julius Shulman photographed it in the 1940s, with the San Jacinto Mountains as the backdrop. Later, photographer Slim Aarons captured the home — and some say the spirit of modernism — in his 1970 photo Poolside Gossip.

The recognizable pool was only one portion of the landscape featured on the tour, as the property has four distinct courtyards designed to accommodate specific uses, microclimates and privacy needs. All have been meticulously restored, and we’ll be touring them here.

Fallingwater in Mill Run, Pennsylvania. Photo by Colin Flavin

Wright and Neutra: Architectural Rivals

This was not the Kaufmanns’ first time commissioning an iconic house. Eleven years earlier, Frank Lloyd Wright designed Fallingwater as their weekend home in the countryside outside Pittsburgh. They found the winters of rural Pennsylvania too cold and scouted Palm Springs for a winter getaway.

Naturally, Wright was on their short list. They toured his Arizona desert home and studio, Taliesin West, to see his organic approach to designing in the desert, where stone, concrete and timber merged with the environs. The Kaufmanns ultimately hired Neutra to create a more austere version of a modern house in the desert.

Wright and Neutra: Architectural Rivals

This was not the Kaufmanns’ first time commissioning an iconic house. Eleven years earlier, Frank Lloyd Wright designed Fallingwater as their weekend home in the countryside outside Pittsburgh. They found the winters of rural Pennsylvania too cold and scouted Palm Springs for a winter getaway.

Naturally, Wright was on their short list. They toured his Arizona desert home and studio, Taliesin West, to see his organic approach to designing in the desert, where stone, concrete and timber merged with the environs. The Kaufmanns ultimately hired Neutra to create a more austere version of a modern house in the desert.

Liliane Kaufmann reclines poolside at the Kaufmann House in 1947. Archival photo by Julius Shulman, J. Paul Getty Trust

Photo by Joe Fletcher

Desert Modern

In contrast to Wright’s organic method, Neutra’s Kaufmann House has more in common with the International Style in Europe, with its machine-like appearance that stands out against the surrounding desert. Neutra’s design is carefully calibrated to its setting. Walls of glass open to the south and east and are protected from the sun with broad overhangs. Indoor and outdoor spaces seamlessly merge, with concrete floors extending from inside to out.

Thick Utah buff sandstone and stucco walls with few windows dominate the north- and west-facing sides to protect the house from the prevailing cold winter winds and occasional sandstorms.

Desert Modern

In contrast to Wright’s organic method, Neutra’s Kaufmann House has more in common with the International Style in Europe, with its machine-like appearance that stands out against the surrounding desert. Neutra’s design is carefully calibrated to its setting. Walls of glass open to the south and east and are protected from the sun with broad overhangs. Indoor and outdoor spaces seamlessly merge, with concrete floors extending from inside to out.

Thick Utah buff sandstone and stucco walls with few windows dominate the north- and west-facing sides to protect the house from the prevailing cold winter winds and occasional sandstorms.

The Grace Miller House, with the snow-covered San Jacinto Mountains in the background. Photo by Colin Flavin

Neutra was instrumental in establishing the desert modern aesthetic, characterized by sleek forms and walls of glass that invite indoor-outdoor living. He had learned about building in the harsh climate a decade earlier, in 1937, while designing one of Palm Springs’ first modern homes. Grace Miller, the project’s namesake client, was familiar with the environment and critiqued Neutra’s preliminary plans. She urged him to reorient the house and outdoor spaces to avoid the persistent winds from the north, which he did and also later applied to the Kaufmann House and its garden courts.

Neutra was instrumental in establishing the desert modern aesthetic, characterized by sleek forms and walls of glass that invite indoor-outdoor living. He had learned about building in the harsh climate a decade earlier, in 1937, while designing one of Palm Springs’ first modern homes. Grace Miller, the project’s namesake client, was familiar with the environment and critiqued Neutra’s preliminary plans. She urged him to reorient the house and outdoor spaces to avoid the persistent winds from the north, which he did and also later applied to the Kaufmann House and its garden courts.

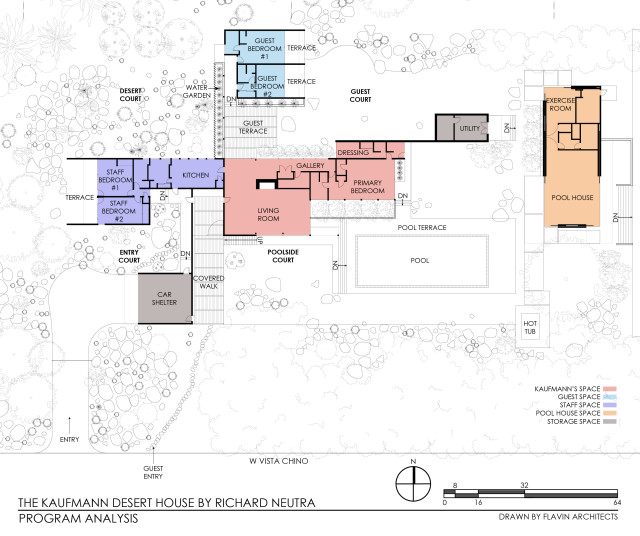

The floor plan is color-coded to show the Kaufmanns’ space in red, guest wing in blue, staff wing in purple, the later added pool house in orange and storage spaces in gray.

Interlocking House and Landscape

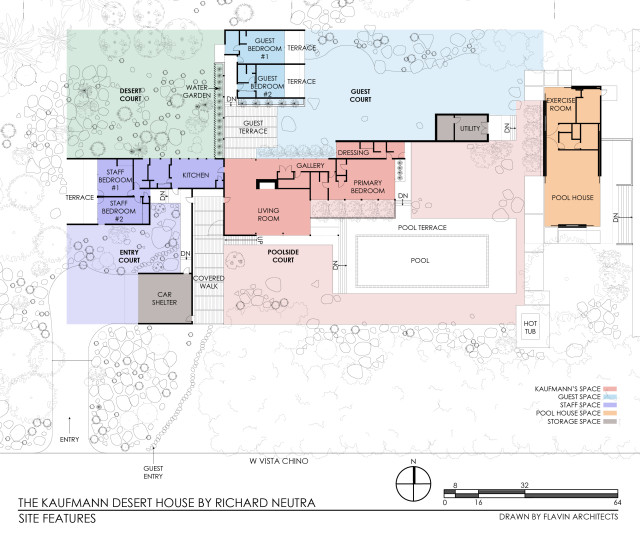

Neutra arranged the floor plan with four wings in the shape of a pinwheel, with the long axis of the building oriented in an east-west direction and the short axis in a north-south direction. The living room, dining room and primary bedroom occupy the east wing; the carport and entry occupy the south wing; the kitchen and staff quarters occupy the west wing; and the guest quarters occupy the north wing.

This arrangement provides privacy for the different uses of the home’s interior and divides the surrounding landscape into four courtyards, each with different exposure to the desert environment. The courtyard spaces become an extension of the building’s interior.

Interlocking House and Landscape

Neutra arranged the floor plan with four wings in the shape of a pinwheel, with the long axis of the building oriented in an east-west direction and the short axis in a north-south direction. The living room, dining room and primary bedroom occupy the east wing; the carport and entry occupy the south wing; the kitchen and staff quarters occupy the west wing; and the guest quarters occupy the north wing.

This arrangement provides privacy for the different uses of the home’s interior and divides the surrounding landscape into four courtyards, each with different exposure to the desert environment. The courtyard spaces become an extension of the building’s interior.

The southwest-facing entry court. Desert materials and plantings are invited into the gardens, and plant choices respond to the home’s orientation and the microclimate it creates. Photo by Dan Solomon

Entry Court

The most utilitarian outdoor garden space of the project, the entry court, is designed for deliveries, parking and drop-offs. Because it’s a circulation space, its orientation to the brutal southwestern afternoon sun has less of an effect on its use.

Native boulders are piled high to create privacy from the street and provide an ideal setting for heat-loving native plants, including ocotillo, smoketree and deergrass. A path with random cut sandstone leads from the carport and driveway to the home’s service entrance. Neutra designed the walls surrounding this space with almost no glass to keep any extra heat from entering the house.

Entry Court

The most utilitarian outdoor garden space of the project, the entry court, is designed for deliveries, parking and drop-offs. Because it’s a circulation space, its orientation to the brutal southwestern afternoon sun has less of an effect on its use.

Native boulders are piled high to create privacy from the street and provide an ideal setting for heat-loving native plants, including ocotillo, smoketree and deergrass. A path with random cut sandstone leads from the carport and driveway to the home’s service entrance. Neutra designed the walls surrounding this space with almost no glass to keep any extra heat from entering the house.

The desert court, with the first-floor passage lined with vertical louvers. On the second floor, the gloriette roof deck is protected by louvers on its north and west sides. Photo by Dan Solomon

Desert Court

The desert court faces northwest, also a severe orientation, exposed not only to the heat of the afternoon sun but also to chilly winter winds. The landscape is designed to emulate the natural desert, with boulders artfully arranged in a field of sand and cactus. The garden has no direct access from the house and is intended to be seen only from the covered walk leading from the living wing to the guest wing.

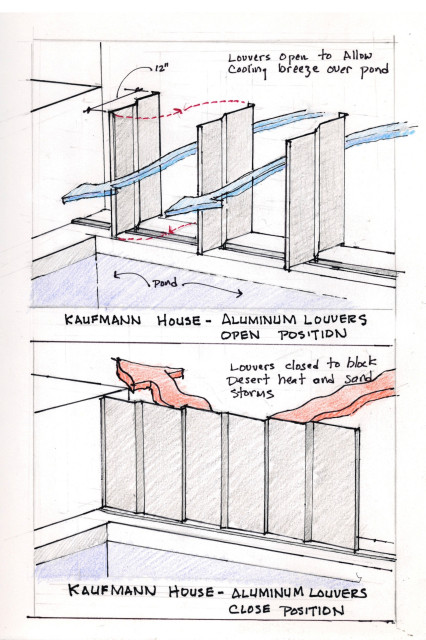

A linear pool of water lines the west side of the covered walk, with an ingenious line of vertical aluminum louvers. These can be adjusted to open to the desert garden, admitting a cooling breeze over the water, or be closed to block the afternoon sun.

Desert Court

The desert court faces northwest, also a severe orientation, exposed not only to the heat of the afternoon sun but also to chilly winter winds. The landscape is designed to emulate the natural desert, with boulders artfully arranged in a field of sand and cactus. The garden has no direct access from the house and is intended to be seen only from the covered walk leading from the living wing to the guest wing.

A linear pool of water lines the west side of the covered walk, with an ingenious line of vertical aluminum louvers. These can be adjusted to open to the desert garden, admitting a cooling breeze over the water, or be closed to block the afternoon sun.

The outdoor passage between the guest rooms in the foreground and main residence beyond. The vertical louvers line the right side of the pool of water and face the desert court. Photo by Dan Solomon

In these cutaway diagrams, Neutra’s ingenious louver system is shown open in the upper drawing and closed in the lower. Sketch by Colin Flavin

The intimate guest courtyard, with a view of the desert court beyond. Photo by Joe Fletcher

Guest Court

The intimate guest court is shared between the guest and living wings and is the most enclosed of the outdoor spaces. It functions as an outdoor living room, surrounded by walls on three sides and protected from the high winds from the north and the occasional sandstorm. The courtyard is a perfect space for the owners and guests to meet, with planks of concrete paving and lounge seating.

Guest Court

The intimate guest court is shared between the guest and living wings and is the most enclosed of the outdoor spaces. It functions as an outdoor living room, surrounded by walls on three sides and protected from the high winds from the north and the occasional sandstorm. The courtyard is a perfect space for the owners and guests to meet, with planks of concrete paving and lounge seating.

Walls of glass extend the living room into the garden on the south-facing side of the house. The architecture’s precise lines continue in the landscape terraces, swimming pool and planters. Photo by Dan Solomon

Poolside Court

Facing southeast, the poolside court has the most favorable orientation for outdoor living — it receives the morning and midday sun, but hot afternoon sun and cold northern breezes are blocked by the house. The living room’s polished concrete floors extend into the yard to create a crisply detailed terrace and swimming pool deck. The pool and deck match the dimensions of the living room and primary bedroom, underlining that the outdoor living space is integral to the ensemble.

Poolside Court

Facing southeast, the poolside court has the most favorable orientation for outdoor living — it receives the morning and midday sun, but hot afternoon sun and cold northern breezes are blocked by the house. The living room’s polished concrete floors extend into the yard to create a crisply detailed terrace and swimming pool deck. The pool and deck match the dimensions of the living room and primary bedroom, underlining that the outdoor living space is integral to the ensemble.

The site plan is color-coded to show the exterior spaces in a lighter tone of the same color as their corresponding interior spaces.

House and Garden Restoration

Brent and Beth Harris purchased the property in 1993, following a series of notable owners that included San Diego Chargers owner Gene Klein and singer Barry Manilow. With large additions made over the years, the approximately 3,000-square-foot original house had nearly doubled in size, extending into the courtyard spaces and losing much of Neutra’s original landscape design intent.

Soon after purchasing the home, the Harrises hired Los Angeles firm Marmol Radziner to act as architect, designer, landscape architect and builder to restore the property and add a pool house. Architect Leo Marmol credits the client with being “the real hero” and never compromising in the effort to return to the original Neutra design.

According to Marmol, it was 120 degrees outside when they first visited the property in August 1992. “The landscape was more of a suburban wonderland with very little desert attributes to the garden itself,” he says. Beneath all the changes, though, they could see “the core Richard Neutra power.… Our mission was truly to take the house back to what it was when it was completed,” he says.

The home had not yet been recognized as a historic property and did not have any preservation requirements. (Since then, it has been designated a Class 1 Historic Site by the Palm Springs City Council.) Instead, it was the clients who drove the historically accurate renovation.

House and Garden Restoration

Brent and Beth Harris purchased the property in 1993, following a series of notable owners that included San Diego Chargers owner Gene Klein and singer Barry Manilow. With large additions made over the years, the approximately 3,000-square-foot original house had nearly doubled in size, extending into the courtyard spaces and losing much of Neutra’s original landscape design intent.

Soon after purchasing the home, the Harrises hired Los Angeles firm Marmol Radziner to act as architect, designer, landscape architect and builder to restore the property and add a pool house. Architect Leo Marmol credits the client with being “the real hero” and never compromising in the effort to return to the original Neutra design.

According to Marmol, it was 120 degrees outside when they first visited the property in August 1992. “The landscape was more of a suburban wonderland with very little desert attributes to the garden itself,” he says. Beneath all the changes, though, they could see “the core Richard Neutra power.… Our mission was truly to take the house back to what it was when it was completed,” he says.

The home had not yet been recognized as a historic property and did not have any preservation requirements. (Since then, it has been designated a Class 1 Historic Site by the Palm Springs City Council.) Instead, it was the clients who drove the historically accurate renovation.

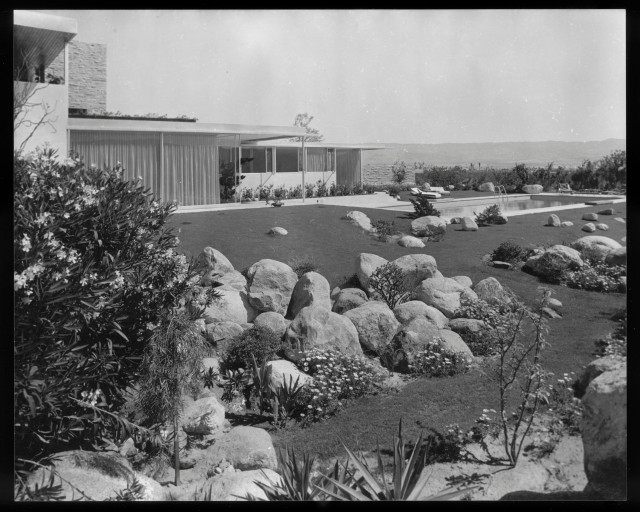

Neutra placed more boulders on the lawn surrounding the pool terrace in his original design. Native plantings are seen in the foreground. Archival photo by Julius Shulman, J. Paul Getty Trust

The restoration team scoured UCLA’s archives but was unable to find the home’s original architectural drawings. Thankfully, Neutra was diligent in having his work documented by photographer Julius Shulman, and extensive images of the house and landscape from 1947 and 1949 were available. This photographic record turned out to be the best source of archival information available, and Marmol describes “literally using magnifying glasses on those photographs” to understand the original conditions. Working from these photos, the team restored the house and garden nearly to the way it had been designed.

Additionally, the Harrises purchased one lot to the west, one lot to the east and two lots to the north of the home to reestablish the feeling of the house and garden isolated in a desert landscape. “We had the challenge that Mr. Neutra did not: a suburban city growing around the site. So we had to look at how to shield what were originally views to the wild desert,” Marmol says.

With the opportunity to expand the site, Marmol Radziner regraded the lots to revive the original landscape design. The Kaufmanns originally had worked with Chester “Cactus Slim” Moorten, a local landscaper who owned Moorten Botanical Garden, to introduce a desert landscape to the property. The team collaborated with Moorten’s son, working together to restore the Kaufmann landscape to its original design.

After Marmol Radziner completed its work, landscape architect and current chairman of Modernism Week William Kopelk continued on the project, designing a garden to the east and helping the Harrises select resilient native plantings.

The restoration team scoured UCLA’s archives but was unable to find the home’s original architectural drawings. Thankfully, Neutra was diligent in having his work documented by photographer Julius Shulman, and extensive images of the house and landscape from 1947 and 1949 were available. This photographic record turned out to be the best source of archival information available, and Marmol describes “literally using magnifying glasses on those photographs” to understand the original conditions. Working from these photos, the team restored the house and garden nearly to the way it had been designed.

Additionally, the Harrises purchased one lot to the west, one lot to the east and two lots to the north of the home to reestablish the feeling of the house and garden isolated in a desert landscape. “We had the challenge that Mr. Neutra did not: a suburban city growing around the site. So we had to look at how to shield what were originally views to the wild desert,” Marmol says.

With the opportunity to expand the site, Marmol Radziner regraded the lots to revive the original landscape design. The Kaufmanns originally had worked with Chester “Cactus Slim” Moorten, a local landscaper who owned Moorten Botanical Garden, to introduce a desert landscape to the property. The team collaborated with Moorten’s son, working together to restore the Kaufmann landscape to its original design.

After Marmol Radziner completed its work, landscape architect and current chairman of Modernism Week William Kopelk continued on the project, designing a garden to the east and helping the Harrises select resilient native plantings.

The path to the front door shows Neutra’s unique striated concrete paving pattern. The tall ocotillo plant on the right in front of the staircase to the gloriette is original to the house. Photo by Dan Solomon

Another challenge for Marmol Radziner was reproducing the home’s materials and details that had been removed by previous owners. Bright white concrete terraces and walkways were an integral part of the original design. The team experimented with how to re-create the finish; it eventually settled on a custom mix of white sand and white Lehigh cement with a ground finish. The concrete was given a polished finish on the interior; on the exterior it was acid-etched for slip resistance.

Many of the original adjustable vertical aluminum louvers that gave the home its distinctive appearance and shielded the outdoor spaces from the sun were missing or damaged. Marmol Radziner’s metal shop re-created the S-shaped interlocking fins.

Another challenge for Marmol Radziner was reproducing the home’s materials and details that had been removed by previous owners. Bright white concrete terraces and walkways were an integral part of the original design. The team experimented with how to re-create the finish; it eventually settled on a custom mix of white sand and white Lehigh cement with a ground finish. The concrete was given a polished finish on the interior; on the exterior it was acid-etched for slip resistance.

Many of the original adjustable vertical aluminum louvers that gave the home its distinctive appearance and shielded the outdoor spaces from the sun were missing or damaged. Marmol Radziner’s metal shop re-created the S-shaped interlocking fins.

The view from the second-story gloriette. Neutra was able to skirt zoning laws, which did not allow for two-story homes in Palm Springs at the time of construction, and build an open-air perch with a roof and louvers to block the sun and wind. Photo by Dan Solomon

The Kaufmann House as seen from the street. Photo by Colin Flavin

Strategic placement of boulders to resemble the natural desert was integral to the original design, but many stones had been moved or taken away over the years. Using the Shulman photos, the team replaced them in generally the original locations; in some instances, the design was adapted to accommodate Palm Springs’ current conditions. At the entry, boulders were piled high and interspersed with desert plantings for privacy.

The team planted three rows of African sumac on the southern perimeter and pruned them to create a hedge, blocking most views of the house from the street. The strong lines of the landscape don’t extend out there. Instead, sandstone footpaths meander to connect the home to the main road, enhancing Neutra’s idea of a “Machine in the Desert.”

Strategic placement of boulders to resemble the natural desert was integral to the original design, but many stones had been moved or taken away over the years. Using the Shulman photos, the team replaced them in generally the original locations; in some instances, the design was adapted to accommodate Palm Springs’ current conditions. At the entry, boulders were piled high and interspersed with desert plantings for privacy.

The team planted three rows of African sumac on the southern perimeter and pruned them to create a hedge, blocking most views of the house from the street. The strong lines of the landscape don’t extend out there. Instead, sandstone footpaths meander to connect the home to the main road, enhancing Neutra’s idea of a “Machine in the Desert.”

The Marmol Radziner pool house design preserves the view of sunrise from the primary bedroom and living room of the Kaufmann House, as conceived by Neutra. Photo by Dan Solomon

Pool House and Viewing Pavilion

During the renovation, the client and architecture team were adamant about returning the house to its original design, with no attached additions. Their central question became how to accommodate a pool house without detracting from the original Neutra masterpiece.

When asked what adding the pool house to the property was like, Marmol says: “Well, it was horrifying. My god, putting a building close to the Kaufmann House? I mean, it was both our greatest dream and worst nightmare.

“Our goal was to, of course, be responsive to the modern character of the original home but clearly be distinct from the Kaufmann House. The pool house had to be legibly not part of the historic experience,” Marmol says. “So other than its modern detailing, there’s no visual connection.… The design had to be visually separated from the Kaufmann House.”

Pool House and Viewing Pavilion

During the renovation, the client and architecture team were adamant about returning the house to its original design, with no attached additions. Their central question became how to accommodate a pool house without detracting from the original Neutra masterpiece.

When asked what adding the pool house to the property was like, Marmol says: “Well, it was horrifying. My god, putting a building close to the Kaufmann House? I mean, it was both our greatest dream and worst nightmare.

“Our goal was to, of course, be responsive to the modern character of the original home but clearly be distinct from the Kaufmann House. The pool house had to be legibly not part of the historic experience,” Marmol says. “So other than its modern detailing, there’s no visual connection.… The design had to be visually separated from the Kaufmann House.”

Glass sliding doors pocket out of sight to open the view to the Kaufmann House. Photo by Dan Solomon

Marmol placed the pool house east of the iconic pool terrace and conceived the structure as a viewing pavilion for the original house. The view from the seating area re-creates the view of the house with the San Jacinto Mountains in the background that Julius Shulman (and later Slim Aarons) made famous.

The Harrises decreased the property’s overall amount of lawn during the renovation to embrace the natural desert landscape more fully. They chose to keep the green carpet of grass around the pool and guest courts, however, to stay faithful to Neutra’s vision and to maintain the iconic view of the home that is recognizable around the world.

Marmol placed the pool house east of the iconic pool terrace and conceived the structure as a viewing pavilion for the original house. The view from the seating area re-creates the view of the house with the San Jacinto Mountains in the background that Julius Shulman (and later Slim Aarons) made famous.

The Harrises decreased the property’s overall amount of lawn during the renovation to embrace the natural desert landscape more fully. They chose to keep the green carpet of grass around the pool and guest courts, however, to stay faithful to Neutra’s vision and to maintain the iconic view of the home that is recognizable around the world.

Source: www.Houzz.com

Neutra designed the house and landscape, which were completed in 1946, for Pittsburgh department store owners Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann as their winter vacation home. Considered by many to be the greatest example of desert modernism, the Kaufmann House helped define how modern architecture could complement the harsh desert environment and influenced a generation of architects in Southern California, including Albert Frey, William Krisel and Donald Wexler.